The Beatles and You

Published in Goal Setting, Problem SolvingReminders of Persistence, Potential and Performance

A version of this blog first appeared in Greg Bustin’s book Decision Time: Inspiration, Insight & Wisdom from History’s Make-or-Break Moments.

You’ve heard that it was twenty years ago today that Sergeant Pepper taught the band to play, but it was sixty-five years ago this week that George Martin taught the Beatles how to make the most of their potential.

That day – June 6, 1962 – launched the partnership between the Beatles and George Martin, transforming a scruffy band with talent into the most influential band in Western popular music and the bestselling band in history.

By 1962, the Beatles had been playing together for two years. They’d secured gigs in Hamburg, written and performed their own songs and secured the top spot above more than five hundred local groups in Mersey Beat’s first popularity poll. They were drawing crowds at Liverpool’s Cavern Club.

But to take the next step, to escape the grind of playing the same songs night after night, six nights a week, the Beatles needed a recording contract. And the chances of securing one were evaporating.

Brian Epstein owned a Liverpool record shop and he orchestrated a meeting with the group then began representing the Beatles without pay and without a contract. Epstein arranged an audition with Decca on New Year’s Day 1962. It was snakebit from the start with missed notes, nervous vocals and zero showmanship. Decca’s Dick Rowe and Mike Smith rejected them, saying “Guitar groups are on the way out.”

On January 24, the group swapped manager Allan Williams for Brian Epstein, but it was almost too late. As the Beatles new manager, Epstein faced one rejection after another. Yet he was passionate and persistent.

By the time Epstein arranged a February 13 meeting with EMI producer George Martin, even Martin’s colleague Sid Coleman noted the Beatles “had been rejected by everybody, absolutely everybody in the country.” That meeting between Epstein and Martin ended without a commitment from Martin. So Epstein was surprised when he was invited to a May 9 meeting with Martin. Epstein played Martin a tape. “You know,” said Martin, hedging his bets, “I really can’t judge it, on what you’re playing me here. Bring them down to London and I’ll work with them in the studio.”

Brian immediately sent the Beatles a telegram while they were booked in Hamburg: “Have secured contract for Beatles to record for EMI on Parlaphone Label. Date set for June 6th.”

What causes me to continue supporting something that isn’t delivering the results I expect?

One Last Chance

Epstein had not secured a contract. He had secured a date for a recorded audition.

Martin later said it would have been “preposterous” to give the Beatles a contract without meeting them and hearing them in person.

But unbeknownst to Epstein and the Beatles, Martin’s contract with EMI was set to expire and he was clashing with his bosses. Parlaphone was EMI’s island of misfits, where Martin produced talents who didn’t fit the mold, such as comedian Peter Sellers. Martin had been directed by his bosses to listen to this scruffy band from Liverpool as a way of putting him in his place. Martin, for his part, began wondering if the Beatles might be his ticket to ride.

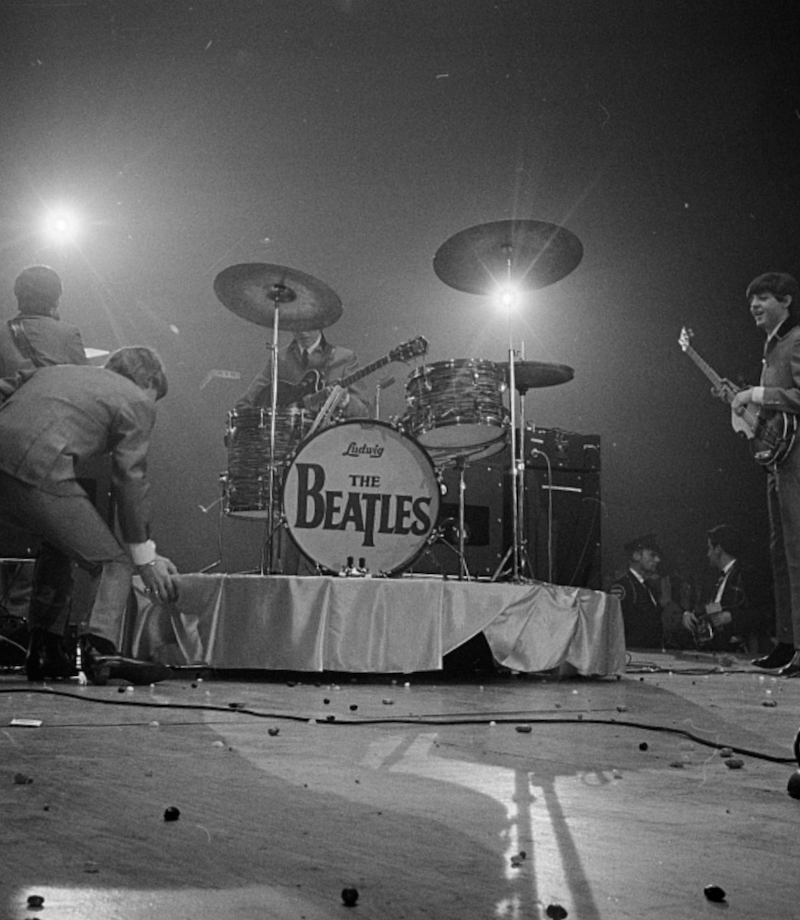

On Wednesday, June 6, the Beatles arrived at the EMI studios with thirty-two songs.

Martin was not present for the audition, directing his colleague Ron Richards to select two or three songs to record. Richards selected two covers (“Besame Mucho” and “Ask Me Why”) and two Lennon-McCartney originals (“Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You”).

The entire audition was touch and go. Realizing this audition might be their final chance to secure a recording contract, the Beatles were nervous and it showed. Engineer Norman Smith said, “They didn’t impress me at all.”

But Lennon’s harmonica playing on “Love Me Do” intrigued Richards and so he invited Martin back to the studio to listen to the recording of the four songs.

Martin listened, trying to decide which Beatle was the leader. That was the convention of the day: a headliner and a backing band. Martin was thinking, “Is it John Lennon and The Beatles or Paul McCartney and The Beatles? I knew it wasn’t George.”

The Beatles didn’t fit the mold.

What longstanding practice, policy or belief is it time to rethink?

Glimpsing What Others Missed

There was another bigger problem. Despite years of performing together, the band’s playing was not polished.

After listening to the recording of “Love Me Do,” George Martin left the control room, introduced himself to the band and then made changes to the song – as he would do in their songs to follow – that would make it a hit.

There were still problems with the audition. Following a dinner break, Martin, Richards and Smith critiqued the playback for John, Paul, George and Pete Best. No one mentioned their shared concerns about drummer Pete Best.

Following a lengthy critique, Martin asked the Beatles if there was anything they didn’t like. George Harrison waited a beat then pounced: “I don’t like your tie.” After an uncomfortable silence, Martin noticed a slight smile from George then began laughing. “That was the turning point,” said Norman Smith. The joke broke the tension, opened a lively bit of wordplay, and gave Martin a glimpse of the boys’ wit, chemistry and potential. But Pete Best had not joined in.

During this animated exchange, Martin made two decisions. He would sign the Beatles despite their mediocre performance, and drummer Pete Best would “have to go.”

It wasn’t their music that secured the Beatles their contract. It was their personalities.

What’s our approach for identifying and developing potential?

Getting the Best from Talent

The Beatles were stubborn. They also knew they were stuck.

They had achieved a level of success but realized they would be bored playing the same songs every night. They were ambitious. They wanted more. But they didn’t know how to get better.

Because of these factors, they accepted Martin’s coaching. “George had done no rock and roll and we’d never been in a studio,” said Lennon, “so we did a lot of learning together. He had a very great musical knowledge and background.”

“If I, too, had turned them down,” Martin later said, “it’s very hard to guess what would’ve happened. Probably they would’ve broken up, and never have been heard from again.”

Under the tutelage of Martin, the Beatles replaced Pete Best with Ringo Starr, released seven albums in four years, and achieved worldwide acclaim.

“The Beatles had marvelous ears when it came to writing and arranging their material,” says Martin’s colleague Ron Richards, “but George [Martin] had real taste—and an innate sense of what worked.”

Martin pushed the Beatles and the Beatles responded.

Rubber Soul, released December 3, 1965, broke new ground in lyrics, instrumentation and the band’s approach to an album.

Revolver, released August 5, 1966, has become recognized as the most innovative album in the history of popular music with double-tape loops, overdubs and orchestral instrumentation. It signaled the end of the Beatles touring career.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released May 26, 1967, is an early form of a concept album. Recording the entire album spanned one hundred twenty-nine days, or seven hundred hours. Total time spent recording the final track on Sgt. Pepper—“A Day in The Life”—took thirty-four hours. Their first album—Please Please Me—was recorded in ten hours and forty-five minutes.

Where can we break with convention, the status quo and the predictable and deliver something new?

You can do great things, too. You just need a little help from your friends.

Ready to reset?

Attend my free Accountability webinar: I Did It! to set and achieve your 2021 goals.

- February 17th from 11 AM – 12:30 PM Central Time

- My free webinar will help you:

– Sharpen your personal goals

– Improve time management

– Tackle tough work-related issues

– Support remote workers

Learn More

To dive even deeper into the topic of accountability, I invite you to purchase a copy of my bestselling book, “Accountability: The Key to Driving a High-Performance Culture.”

Become a better leader.

Download my three free e-books.

Free Tips

Sign up to receive free tips on business, leadership, and life.

Get My Latest Book

HOW LEADERS DECIDE

History has much to offer today’s current and aspiring leaders.

Business schools teach case studies. Hollywood blockbusters are inspired by true events.

Exceptional leaders are students of history. Decision-making comes with the territory.