The CEO’s New Clothes

Published in LeadershipSome Leaders Can’t Handle the Truth

The CEO of my business unit’s parent company called me to his office to tell me he had acquired a cross-town rival. My former competitor would soon be my boss.

Though I was leading the business unit affected by this move, the CEO didn’t consult me. I was thirty-eight years old, confident and outspoken. I told the CEO the acquisition was a bad idea because our cultures weren’t compatible.

“I’m not asking for your opinion,” the CEO shot back. “I’m informing you. And I expect the two of you to work together to grow the business.”

So ninety days after our two companies merged, my new boss and I were meeting over lunch to discuss how things were going. Based on my relationships within the firm my boss figured I was tapped into what people were really saying. I delivered my assessment.

I don’t remember what I ordered for lunch that day but I do remember losing my appetite.

A Fairy Tale Speaks to Us Today

Hans Christian Andersen was a Danish author best remembered for his fairy tales, including “The Little Mermaid,” “The Ugly Duckling,” “The Princess and the Pea,” and “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” which was first published this month in 1837.

You recall the story: A fabric of lies is woven from elements of vanity, greed and fear.

Two con men call at the court of a vain Emperor, promising to weave gorgeous garments made from materials so beautiful they can only be seen by very smart and clever people. The Emperor, believing he can “find out at once” those in his kingdom who “are not good enough for the positions they hold,” falls for the scam, paying the knaves excessively and ordering silks, golden thread and looms to be delivered so the fake weavers can begin their work at once.

The rogues maintain a charade of weaving, requesting more of the finest material, which they stow away for themselves.

The Emperor, keen to learn how work is progressing but concerned he might be unable to see the material, dispatches his trusted minister. The minister visits the con men, sees nothing on the looms but continues the charade, reporting back to the Emperor “how very wonderful” everything looks. Other officers of the court visit the con men and the result is the same: While no one can see anything, everyone is scared to expose the ruse for fear of losing his job.

The non-existent clothes are delivered to the emperor and the rogues exclaim, “The whole suit is as light as a cobweb.” The emperor thinks, “I can see nothing. Am I a stupid man, or am I unfit to be Emperor?” [See Imposter Syndrome.] Instead, he says, “The cloth is beautiful. I am delighted with it.”

Donning the imaginary garments, the Emperor leads a procession through the town in his birthday suit. The townsfolk are unsettled but, having heard of the garments’ magical powers, continue the pretense, not wanting to appear foolish.

Suddenly a child yells, “But the Emperor has nothing on at all.” Word spreads quickly until everyone admits the Emperor is wearing nothing. The Emperor realizes the people are right but pretends all is well and continues the procession.

What’s it like to speak truth to power in our organization?

Modern-Day Emperors

I’d probably taken great culture for granted – at least until the day the CEO told me he’d acquired my competitor.

The healthy environments where I worked seemed to occur naturally. Talented people collaborated with one another and with clients we respected. We spoke hard truths. We had fun. We produced terrific results. We made money.

Simple? Yes. Easy? Not at all.

Lawyers, accountants, bankers and executives may spend hundreds of hours tightening a deal, yet many times, factors some might call “soft” are the very ones that cause deals to fall apart and mergers to fail over the longer term. Culture is one of these factors.

“You don’t know what you’ve got,” sang Joni Mitchell, “‘till it’s gone.”

You’ve probably already guessed the two different cultures I’d warned my CEO about soon were in conflict. And the assessment I delivered that day at lunch was not the report my new boss wanted to hear. Responses to each hard truth ranged from disbelief to defensiveness to anger (directed, I thought, mostly at me). Before lunch was over, I’d made two decisions: First, I resolved never to say another discouraging word to my boss (even when grounded in fact). Second, I began making plans to find a new job.

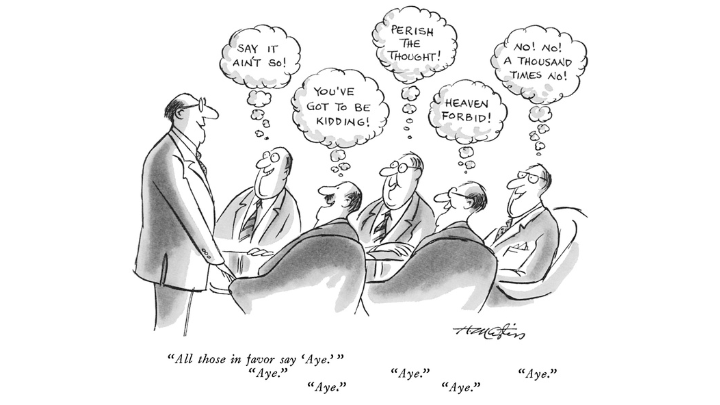

This 1979 cartoon by Henry Martin lampoons modern-day emperors who run their kingdoms where disagreement is discouraged.

Discouraging debate, stifling conflict and suppressing dissent isn’t healthy.

Twelve months after the acquisition, the most talented people were gone. Three years after the acquisition, the boss who had bristled at my assessment was gone, the company was awash in red ink, and I was asked to return and lead the company. I declined.

Four years after the acquisition, the company was in worse shape and I was given the opportunity to purchase that wholly owned subsidiary for cents on the dollar, spin it off and start my own firm. I agreed.

The March issue of Fortune magazine reports the latest findings from the Edelman Trust Barometer, a respected global survey. [I led Edelman’s Dallas office following my departure from my previous post.] “Disturbingly large numbers of people say there’s no one they trust anymore: not the media, corporations, governments, nor NGOs. And they certainly don’t trust CEOs.

When there’s no trust, inconvenient truths are avoided, vigorous discussions are discouraged and useful solutions are few and far between. You can’t fix what you won’t discuss.

Questions to consider:

- On a scale of 1-10 (with 10 being the best), how would I rate the level of trust in our organization?

- When things go sideways and I ignore data, am I lying to others or lying to myself?

- Would I rather be wrong and happy or know the truth and be uncomfortable?

In my work with leadership teams, I can anticipate with reasonable accuracy how well a team will perform by how well the leaders are willing to discuss uncomfortable issues. I’m not a fan of artificial harmony. Though I’m sometimes afraid to say hard truths, I’ll do it because I believe I owe people (and myself) honesty.

“The truth may set you free,” said Gloria Steinem, “but first it will piss you off.”

It’s human nature to become angry when other people’s ideas are in conflict with ours. Great leaders use grains of conflict to produce pearls.

Ready to reset?

Attend my free Accountability webinar: I Did It! to set and achieve your 2021 goals.

- February 17th from 11 AM – 12:30 PM Central Time

- My free webinar will help you:

– Sharpen your personal goals

– Improve time management

– Tackle tough work-related issues

– Support remote workers

Learn More

To dive even deeper into the topic of accountability, I invite you to purchase a copy of my bestselling book, “Accountability: The Key to Driving a High-Performance Culture.”

Become a better leader.

Download my three free e-books.

Free Tips

Sign up to receive free tips on business, leadership, and life.

Get My Latest Book

HOW LEADERS DECIDE

History has much to offer today’s current and aspiring leaders.

Business schools teach case studies. Hollywood blockbusters are inspired by true events.

Exceptional leaders are students of history. Decision-making comes with the territory.