JFK, Nixon and Blind Spots

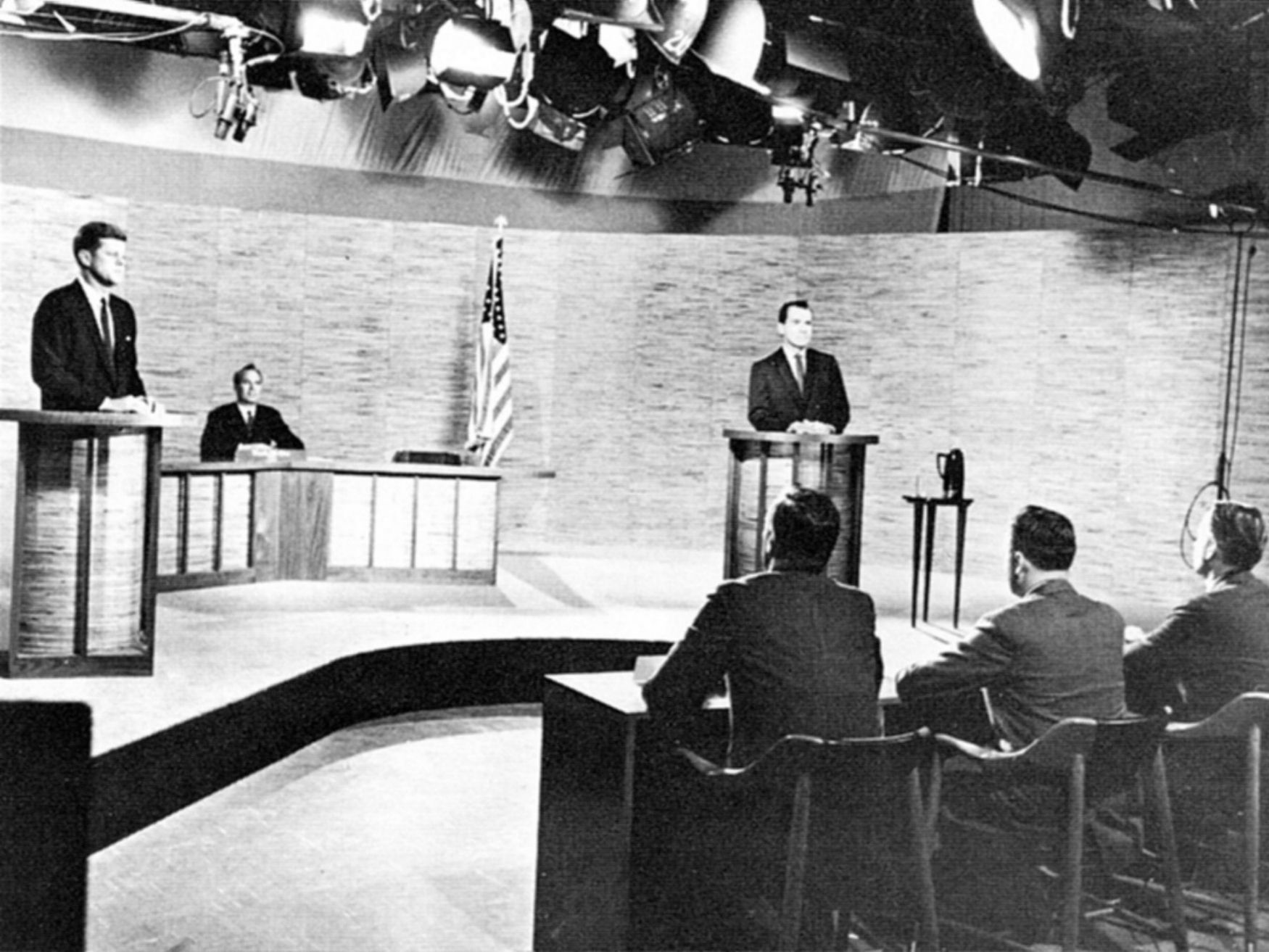

Published in LeadershipSixty years ago this week, Americans experienced the first televised presidential debate in which the two opponents squared off against one another.

The 1960 election pitting Democratic U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy against Republican incumbent Vice President Nixon was notable for three other reasons:

- It was the first election in which all 50 U.S. states participated and the last in which the District of Columbia did not.

- It was the first election in which an incumbent president (Eisenhower) was ineligible to run for a third term.

- This debate inaugurated a new political era where image mattered as much as message.

Nixon, having been hospitalized for an infected knee injury, was not fully recovered and appeared pale, underweight and tired. He refused make-up and so his facial stubble was conspicuous on the black-and-white TV screens. Sweat was visible on his face.

JFK, meanwhile, was tan, fit and cool under fire. His thorough preparation for the debate imparted a confidence in his responses that those of Nixon’s appeared to lack.

After the first televised debate, Nixon’s mother called him to ask if he was sick.

“I was listening to it on the radio,” former Sen. Bob Dole, the GOP’s 1996 presidential nominee, recalled in a PBS interview, “and I thought Nixon was doing a great job. Then I saw the TV clips the next morning, and he … didn’t look well. Kennedy was young and articulate and … wiped him out.”

Kennedy’s good looks and confident, relaxed manner won the night and, six weeks later, the closest presidential election in history.

Television, Kennedy observed, “turned the tide.”

Cognitive Bias

In his June commencement address to the graduating class of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business (of which our daughter Jordan is now a proud alum), serial entrepreneur Bryan Johnson notes there are “188 cognitive biases.”

“What I don’t know,” says the founder of Braintree which acquired Venmo in 2012, “is more important than what I know.”

We all have blind spots. We all contend with bias and false assumptions. The key is how we handle these decision-making traps.

Michael Lewis, author of Liar’s Poker, Moneyball, Blindside and The Big Short, says in his book The Undoing Project that the “new definition of a nerd is ‘someone who knows his own mind well enough to mistrust it.’”

Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in economics and is the author of Thinking, Fast and Slow.

How we frame issues, decisions and discussions often determines the outcomes we get. “Most of us passively accept decision problems as they are framed,” writes Kahneman, and this framing can lead us astray.

Here’s an excerpt from Kahneman’s book that illustrates our decision-making bias with an example that precedes the current COVID-19 pandemic by a decade. Participants were asked to:

Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

If program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

If program B is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved, and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved.

A substantial majority of respondents choose program A: they prefer the certain option over the gamble.

The outcomes of the program are framed differently in a second version:

If program A1 is adopted, 400 people will die.

If program B1 is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-third probability that 600 people will die.

Look carefully and compare the two versions: the consequences of programs A and A1 are identical; so are the consequences of B and B1. In the second frame, however, a large majority of people choose the gamble.

Who illuminates your blind spots?

Beware Your Behavior

Your behavior as a leader sends ripples—that can become tsunamis—throughout your organization.

During the 1960 election between JFK and Nixon, President Eisenhower, who had long been ambivalent about Nixon, held a televised press conference in which Time magazine reporter Charles Mohr mentioned Nixon’s claims that he had been a valuable administration insider and adviser. Mohr asked Eisenhower if he could give an example of a major idea of Nixon’s the president had heeded. Eisenhower responded with the flip comment, “If you give me a week, I might think of one.”

Although both Eisenhower and Nixon later claimed that Ike was merely joking, the damage was done. Democrats turned Eisenhower’s statement into a television commercial.

The words you say, the actions you take, and the way you think affects your organization more than you may realize.

What biases are you carrying? What false assumptions require testing? What signals are you sending?

Ready to reset?

Attend my free Accountability webinar: I Did It! to set and achieve your 2021 goals.

- February 17th from 11 AM – 12:30 PM Central Time

- My free webinar will help you:

– Sharpen your personal goals

– Improve time management

– Tackle tough work-related issues

– Support remote workers

Learn More

To dive even deeper into the topic of accountability, I invite you to purchase a copy of my bestselling book, “Accountability: The Key to Driving a High-Performance Culture.”

Become a better leader.

Download my three free e-books.

Free Tips

Sign up to receive free tips on business, leadership, and life.

Get My Latest Book

HOW LEADERS DECIDE

History has much to offer today’s current and aspiring leaders.

Business schools teach case studies. Hollywood blockbusters are inspired by true events.

Exceptional leaders are students of history. Decision-making comes with the territory.